Инкерманкое сражение,5 ноября 1854 г.,The Battle of Inkerman

- 30.10.11, 11:28

Winner: The British and the French were left holding the field. The Russians withdrew.

British Regiments: Royal Artillery Grenadier Guards Coldstream Guards Scots Fusilier Guards, now the Scots Guards 1st Regiment, the Royal Regiment, now the Royal Scots. 4th the King’s Own Royal Regiment, now the King’s Own Royal Border Regiment. 7th Royal Fusiliers, now the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. 19th Regiment, now the Green Howards. 20th Regiment, later the Lancashire Fusiliers and now the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. 21st Royal North British Fusiliers, now the Royal Highland Fusiliers. 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers. 28th Regiment, later the Gloucestershire Regiment and now the Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Regiment. 30th Regiment, later the East Lancashire Regiment and now the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment. 33rd Regiment, now the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. 38th Regiment, now the Staffordshire Regiment. 41st Regiment, later the Welch Regiment and now the Royal Regiment of Wales. 44th Regiment, later the Essex Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment. 47th Regiment, later the Loyal Regiment and now the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment. 49th Regiment, later the Royal Berkshire Regiment and now the Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Regiment. 50th Regiment, later the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment. 55th Regiment, later the Border Regiment and now the King’s Own Royal Border Regiment. 57th Regiment, later the Middlesex Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment. 63rd Regiment, later the Manchester Regiment and now the King’s Regiment. 68th Regiment, later the Durham Light Infantry and now the Light Infantry. 77th Regiment, later the Middlesex Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment. 88th Regiment, the Connaught Rangers, disbanded in 1922. 95th Regiment, later the Sherwood Foresters and now the Worcestershire and Sherwood Foresters Regiment. The Rifle Brigade, now the Royal Green Jackets. Account: The British, French and Turkish Armies landed on the western coast of the Crimea in the Ukraine on 14th September 1854 intending to capture and destroy the Russian naval port of Sevastopol. The Allied army marched south towards the city, crossing a series of rivers and winning the battle of the Alma (see britishbattles.com). Following the Alma the allied armies could have forced their way into the city, taking advantage of the confusion of defeat and the Russian failure to put Sevastopol in a proper state of defence. The French General St Arnaud and the British commander, Lord Raglan, were unable to agree on a plan of attack. The allies marched around the city, establishing themselves to the East and South and began a formal siege, digging entrenchments and batteries and bombarding the Russian defences. Before the siege began Prince Menshikov took his field army out of Sevastopol, leaving a garrison, and crossed the Tchernaya River to the North East of the city. During October 1854 Menshikov received substantial re-inforcements and was urged by the Tsar, Nicholas II, to take the offensive.

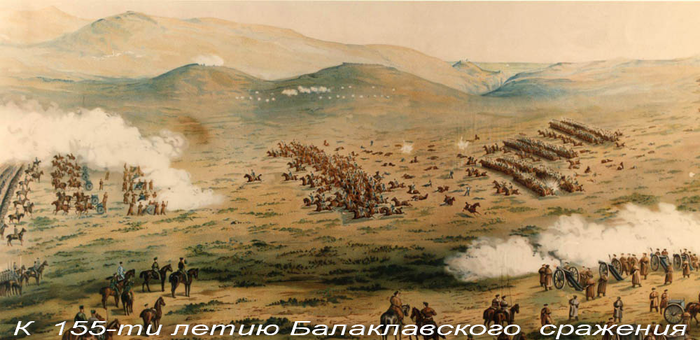

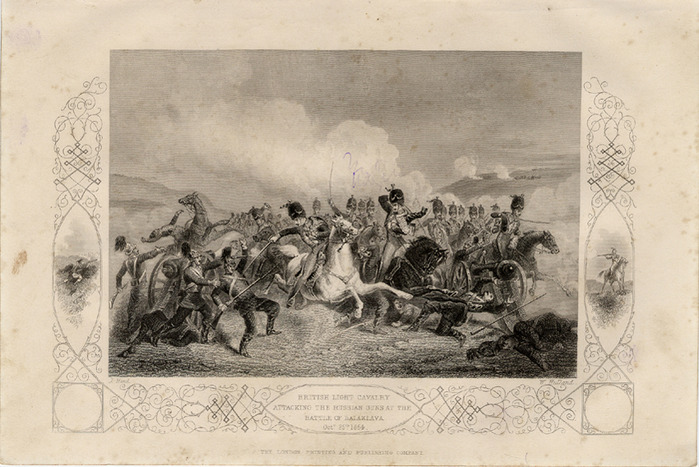

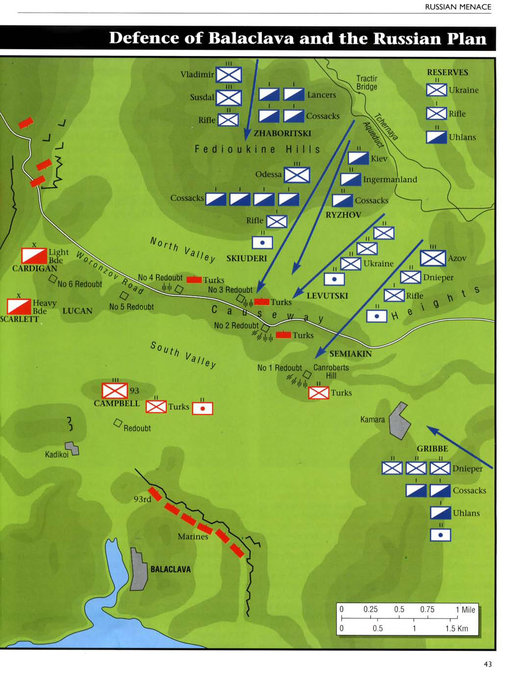

On 25th October 1854 a Russian force under General Liprandi crossed the Tchernaya and advanced on the British base, leading to the battle of Balaclava. Liprandi’s assault was foiled in the battle, during which the charges of the Light Brigade and Heavy Brigade took place, but the Russians were left holding a strong position north of the British line. Balaclava revealed the weakness of the allied position outside Sevastopol. The British and French did not have sufficient troops to man the siege lines around the city and at the same time to oppose the substantial army of Prince Menshikov which was threatening them from across the Tchernaya River.

The Battle of Inkerman: On 5th November 1854 the Russians launched a heavy attack on the right of the allied positions to the east of the city. The attacking force was made up of infantry and guns from the garrison of Sevastopol, commanded by General Soimonoff, and a second column from the field army, commanded by General Pauloff. The two forces, numbering 42,000 men and 134 guns, would come under the overall command of General Dannenberg once they had combined. The attack fell on the British Second Division, comprising 2,700 men and 12 guns. Soimonoff’s advance on the British positions was to be along the southern side of a deep ravine known as the Careenage, moving east. With Pauloff advancing from the north eastern side of the Tchernaya River to join him, the combined force would be in a position to overwhelm the Second Division on the end of the British line, before support could arriv

As dawn broke all the church bells of Sevastopol began a frenzied peel. It was Sunday, but the ringing was to encourage the Russian soldiery rather than to call the faithful to worship. Soimonoff’s columns advanced on Home Hill, 300 riflemen preceding his first line, 6,000 men moving in dense columns. Behind Shell Hill waited the Russian reserve of a further 9,000 men. A number of factors had alerted the Second Division to the imminence of an attack, one being the reconnaissance battle known as Little Inkerman the day after Balaclava. Strong British pickets were in place along the valley to the North West, many at company strength. In the fog these pickets engaged the advancing Russian columns. The firing in the valley gave warning to Brigadier Pennefather, the acting divisional commander, of the beginning of a general action. Pennefather, a highly aggressive officer always inclined to the attack, sent all the units of the Second Division forward to engage the Russians. His actions were exactly appropriate for the day, even though he was committing a small number of troops to battle against overwhelming odds. The Russian heavy artillery on Shell Hill opened a bombardment of the Second Division’s position and camp on Home Ridge. The camp was destroyed but there were no troops on the crest, the division having moved off the ridge into the valley. The Russian infantry, advancing through the drifting fog in dense columns, were met by the British regiments in open skirmishing order or line. The British mini rifled muskets gave quicker, longer ranged and more accurate fire than the Russian flint lock muskets of the Napoleonic period, the cap firing mechanism of the mini infinitely more reliable in the wet conditions. The bottleneck formation of the ground prevented the Russians from making their final approach to Home Ridge on a broad front. The first Russian column to attack emerged from the constricted ground and advanced on the Second Divisions left. A wing of the British 49th Regiment fired a volley into the column and charged with the bayonet, driving the Russian column down the slope and across the valley to Shell Hill. The next assault, also on the Second Division’s left, was in substantially greater numbers and led by General Soimonoff himself. As the Russians approached the ridge, troops of General Buller’s brigade from the Light Division and a battery of guns came up. The 88th Regiment passed the crest followed by the battery, but were driven back, three guns falling into Russian hands. Buller with the 77th Regiment and the 88th charged the column. The 47th Regiment attacked the Russians in flank and the column retreated, giving up the captured guns. General Soimonoff was killed in the struggle and General Buller wounded. A column of Russian sailors attempting an approach from the Careenage Ravine was also attacked by Buller’s men and driven back. The remainder of Soimonoff’s first line advanced down the post road to the Barrier. They were bombarded by a British battery and finally driven back by the assembled British pickets and the remaining companies of the 49th Regiment. The initial Russian assaults had all failed. Soimonoff’s attack took up the first part of the battle. Some of his regiments were so severely handled, losing a high propoertion of officers, that they took no further part in the war. While the struggle had been intense it could not compare with the severity of the fighting that began with the arrival of Pauloff’s force from across the Tchernaya River. Pauloff’s 15,000 men advanced down the axis of the post road towards the northern and north eastern sides of Home Ridge and Fore Ridge. The main focal points of the battle became the Barrier, the Sandbag Battery and the crest of the ridge above them. Pauloff’s attacking line stretched from the post road to the Sandbag Battery. As the Russians advanced, the wing of the British 30th Regiment holding the Barrier, 300 men, leaped the wall and attacked with the bayonet. After a savage fight the leading Russian battalions were driven back down the slope. A further five Russian battalions were assailed by the British 41st Regiment under Brigadier Adams, advancing in extended order. Their intense fire drove this column back to the banks of the Tchernaya River

Brigadier Adams held the Sandbag Battery with 700 men, supported by the 1,300 men of the Guards Brigade. The Russians launched an attack on his position with 7,000 men, beginning a series of charges and countercharges which saw the ground changing hands several times as the fighting raged up and down the hillside. The British were only finally enabled to go on the offensive with the arrival of Cathcart’s Fourth Division. Cathcart’s men were rushed into the line wherever there appeared to be a gap, other than 400 men that Cathcart led himself in a flank attack on the Russians. While initially successful Cathcart was taken in the rear by an unexpected assault from the crest of the ridge. Cathcart was killed and his force broken up. Cathcart’s initiative had the unfortunate effect of encouraging other British units to break from the line and attempt charges down the hill, giving a Russian regiment the opportunity to gain the crest of the ridge. The situation was retrieved by the timely arrival of a French regiment which attacked the Russians in flank and drove them off the ridge. The arrival of further French reinforcements helped to reduce the preponderance of Russian strength and drive them down the hillside. The 21st Regiment still held the Barrier on the post road, although the position had been enveloped by each Russian advance.

At this crisis in the battle the Russians launched a further assault on the left of the Second Division’s position at the exit from the Careenage Ravine, with a second attack on the Home Ridge, bypassing the Barrier. Along the line the Russians reached the crest of the ridge, where a savage struggle developed. But the presence of the French and other British reinforcements was decisive and the Russian attacks were all driven back. During the day the 100 Russian guns on Shell Hill provided a substantial support for their infantry. Towards the end of the battle two large British guns, 18 pounders of modern construction called up by Lord Raglan from the siege park, were manhandled onto Home Ridge by teams of gunners and brought into action. These two guns with the assistance of the field batteries along the line overwhelmed the Russian guns, whose unprotected crews had been subjected to long range rifle fire. Hamley described the end of the fighting saying: “This extraordinary battle closed with no final charge nor victorious advance on the one side, no desperate stand nor tumultuous flight on the other. The Russians, when hopeless of success, seemed to melt from the lost field.” The exhausted English regiments with their French colleagues were left on a field strewn with casualties; the main points of the fighting, the Sandbag Battery and the Barrier, heaped with bodies. The regiments stood down and returned to the siege positions around Sevastopol or to their encampments. Casualties: The British suffered 2,357 casualties. The French suffered 929 casualties. The Russians suffered 12,000 casualties

Follow-up: The Russian attack, although unsuccessful, helped to divert the allies from the siege of Sevastopol, reducing further the prospects of the city being captured before winter and condemning the British and French armies to two winters on the heights. On 14th November 1854 a fierce storm struck the Crimea, wrecking the camps and sinking British and French ships. Much of the limited supply of winter equipment was destroyed and many men drowned.

The Crimean Medal with clasps for each of the battles.

Thanks to Historik Orders of Greenwich, Conn, USA.

Regimental anecdotes and traditions:

References: see the main Crimean War site on britishbattles.com. | |||||||||||||||

|

© britishbattles.com 2010. Email : [email protected] |

The 55th Regiment at the battle of Inkerman

The 55th Regiment at the battle of Inkerman The Battle of Inkerman

The Battle of Inkerman The Roll Call: The men of the 3rd Battalion, Grenadier

Guards, after the Battle of Inkerman. The famous picture that won

acclaim for Lady Butler at the Royal Academy in London.

The Roll Call: The men of the 3rd Battalion, Grenadier

Guards, after the Battle of Inkerman. The famous picture that won

acclaim for Lady Butler at the Royal Academy in London.

The 21st Royal Scots Fusiliers holding the Barrier against

Russian attack at the Battle of Inkerman

The 21st Royal Scots Fusiliers holding the Barrier against

Russian attack at the Battle of Inkerman The Royal Artillery in action

The Royal Artillery in action The British Infantry at the Battle of Inkerman

The British Infantry at the Battle of Inkerman Guards cheering after the Battle of Inkerman.

The Colours in the foreground are those of the Grenadier Guards

Guards cheering after the Battle of Inkerman.

The Colours in the foreground are those of the Grenadier Guards The British Foot Guards attacking the Sandbag Battery: one

of many assaults as the Battery changed hands repeatedly during the

Russian attack at the Battle of Inkerman

The British Foot Guards attacking the Sandbag Battery: one

of many assaults as the Battery changed hands repeatedly during the

Russian attack at the Battle of Inkerman Corporal McDermond of the 47th Regiment winning the

Victoria Cross by saving his wounded colonel from the Russians

Corporal McDermond of the 47th Regiment winning the

Victoria Cross by saving his wounded colonel from the Russians Brigadier General Pennefather the acting commander of the 2nd Division

Brigadier General Pennefather the acting commander of the 2nd Division French Zouaves rescuing a British Guards Officer at Inkerman

French Zouaves rescuing a British Guards Officer at Inkerman

A Sergeant of the Royal Artillery

A Sergeant of the Royal Artillery The death of General Cathcart at Inkerman

The death of General Cathcart at Inkerman Coldstream Guards

Coldstream Guards

<

<

.

.

Все окуталось дымом, и вторая линия Легкой бригады совсем потеряла из вида первую.

Все окуталось дымом, и вторая линия Легкой бригады совсем потеряла из вида первую.

Эту

песню слушало не одно поколение людей нашей страны, звучала она на

стихи Веры Инбер (1890-1972), написанных ею в конце 1920-х годов. Вера

Инбер была двоюродной сестрой Льва Троцкого, одного из главных вождей

Октябрьского переворота в России и организатора Красной Армии, поэтесса и

в советское время продолжала по-родственному общаться с ним. Она жила в

эпоху массового террора, стала лауреатом Сталинской премии за поэму

"Пулковский меридиан", но в нашей памяти осталась лишь как автор песни

"Девушка из Нагасаки". Музыку для песни "Девушка из Нагасаки" написал

композитор Поль Марсель Русаков (1908 - 1973 ), российский еврей из

французского Марселя. Его отец был анархо-коммунистом, участвовал в

демонстрации протеста против интервенции в Советскую Россию, за что его и

выслали в Петроград. Поль Марсель Русаков писал романсы на стихи

Есенина, Блока и Пастернака, потом - СТАЛИН -РОДИНА-ГУЛАГ...

Оригинальный текст песни "Девушка из Нагасаки" многократно исправлялялся

и дополнялся неизвестными соавторами из народа, ее пели известные и не

очень исполнители.

Эту

песню слушало не одно поколение людей нашей страны, звучала она на

стихи Веры Инбер (1890-1972), написанных ею в конце 1920-х годов. Вера

Инбер была двоюродной сестрой Льва Троцкого, одного из главных вождей

Октябрьского переворота в России и организатора Красной Армии, поэтесса и

в советское время продолжала по-родственному общаться с ним. Она жила в

эпоху массового террора, стала лауреатом Сталинской премии за поэму

"Пулковский меридиан", но в нашей памяти осталась лишь как автор песни

"Девушка из Нагасаки". Музыку для песни "Девушка из Нагасаки" написал

композитор Поль Марсель Русаков (1908 - 1973 ), российский еврей из

французского Марселя. Его отец был анархо-коммунистом, участвовал в

демонстрации протеста против интервенции в Советскую Россию, за что его и

выслали в Петроград. Поль Марсель Русаков писал романсы на стихи

Есенина, Блока и Пастернака, потом - СТАЛИН -РОДИНА-ГУЛАГ...

Оригинальный текст песни "Девушка из Нагасаки" многократно исправлялялся

и дополнялся неизвестными соавторами из народа, ее пели известные и не

очень исполнители.

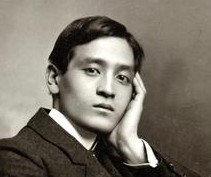

Японский поэт Такубоку Исикава

Японский поэт Такубоку Исикава